Query

Please provide an overview of the available evidence on whether improving the integrity of elections can reduce corruption.

Introduction

Electoral integrity: Definition and measurement

Elections provide a basic tool for citizens to hold political officeholders accountable, Trust in the integrity of elections is essential for a functioning democracy (González et al. 2024). When elections function properly, they can contribute to deepening citizen engagement, improving government responsiveness and informing public debate, among other positive outcomes (Norris and Grömping 2019: 4; Norris 2023). However, elections often fail to meet basic integrity standards, most acutely when electoral fraud or other malpractices undermine electoral competition and result in a lack of a level playing field (see Garnett et al. 2023; Norris 2023).

There are competing conceptualisations of electoral integrity in the academic literature. Van Ham (2015: 716-717) identified 24 studies that conceptualise electoral integrity, which can be distinguished based on three aspects. The first aspect is whether electoral integrity is defined positively or negatively. Positive conceptualisations define electoral integrity by specifying the presence of certain criteria, using terms such as free and fair elections, clean elections and election quality (see: Elklit and Svensson 1997; Lindberg 2006; Munck 2009). On the other hand, negative conceptualisations of electoral integrity stress the absence of aberrations such as electoral fraud or electoral manipulation (van Ham 2015: 716; see: Pastor 1999; Schedler 2002; Birch 2011; López-Pintor 2010).

The second aspect is whether electoral integrity is defined using particular or universal criteria. Universal approaches define electoral integrity by a universal democratic standard (typically based on democratic theory or international law), while particularistic approaches define it in reference to citizens and parties involved (van Ham 2015: 719).

The third aspect is whether electoral integrity is defined using a process or concept-based approach. Concept-based approaches define electoral integrity based on ideal democratic standards, while process-based approaches focus on the electoral cycle and processes as they occur prior to, during and after election day (van Ham 2015: 719).

These different conceptualisations have implications for operationalisation and measurement. Negative definitions, which typically focus on actors and intentionality, are arguably harder to measure due to difficulties in distinguishing between intentional acts and organisational incapacity (van Ham 2015: 718). Further, since particularistic definitions may be more sensitive to context as elections differ in different settings, they may not be appropriate for comparative cross-country studies (van Ham 2015: 719).

This is the argument brought by Norris (2013), who defines electoral integrity positively, using universal criteria. In this conceptualisation, electoral integrity refers to “international conventions and global norms, applying universally to all countries worldwide throughout the electoral cycle” (Norris 2013: 564). Norris (2013: 568) develops this definition by challenging the existing approaches, which they argue are less suitable for comparative studies than a more comprehensive framework derived from global norms. For instance, they point out that a legalistic approach to electoral integrity, focusing on electoral fraud, is not suitable for comparative analysis as elections in autocracies can be in line with the domestic legal framework but still violate widely supported normative standards (Norris 2013: 568). Norris’ conceptualisation has gained traction and has been embraced by the Electoral Integrity Project’s (PEI) Index.

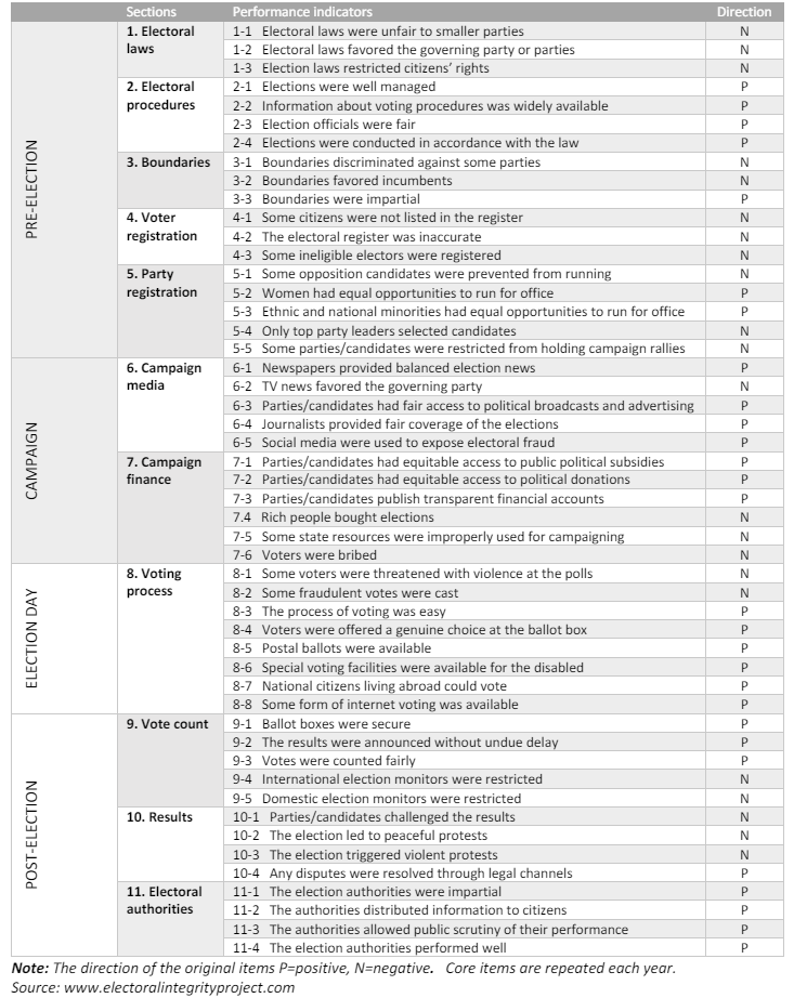

There are different approaches to measuring electoral integrity in the literature once the phenomenon has been conceptualised. Various data sources are used to measure electoral integrity, including election observation reports, news media, historical sources, public and country expert surveys, ethnographic studies and other sources541eb973c508 (van Ham 2015: 723; Birch 2011;; Garnett and James 2020). The PEI index is a leading cross-country dataset based on expert surveys. There are eleven sub-dimensions for which experts provide their assessment, including: electoral laws; electoral procedures; district boundaries; voter registration; party registration; media coverage; campaign finance; voting process; vote count; results; and electoral authorities (Garnett et al. 2023). These sub-dimensions cover the pre-election, campaign, election day and post-election phases.

Figure 1. PEI core survey questions

Source: Garnett et al. 2023: 16

Assumptions about electoral integrity and corruption

In the literature, there is a general assumption that free, fair and competitive elections have a constraining effect on corruption (De Vries and Solaz 2017: 392). One of the main arguments is the electoral accountability (or less frequently “voter punishment”) theory, which holds that because voters generally dislike corruption, they are likely to sanction politicians who misuse public office for private gain (Klašnja 2016a; De Vries and Solaz 2017). In response, politicians are expected to restrain from corrupt behaviour out of fear they would lose elections. An expansion of this argument is that if a higher level of electoral integrity facilitates a more direct translation of voter preferences into official electoral outcomes, it becomes easier for voters to hold corruption officials accountable which in turn ought to disincentivise politicians from corruption.

Different aspects of electoral integrity are assumed to contribute to this causal relationship. For example, strong transparency and oversight mechanisms, enforced through independent institutions, such as agencies regulating and monitoring political finance, or independent electoral management bodies (EMBs), can ensure a transparent voting process. These mechanisms are expected to make corruption easier to detect, acting as a deterrent to politicians’ corrupt behaviour (Hummel et al. 2019; Szakonyi 2021). The type of oversight mechanisms governing the electoral process, particularly the role and powers of EMBs, are believed to be important for safeguarding electoral integrity (van Ham and Lindberg 2015; Norris 2023). Electoral rules enhancing political accountability such as the possibility of judicial punishment are also theorised to constrain corruption by acting as a deterrent to politicians (see Ferraz and Finan 2011).

Another reason why greater electoral integrity is assumed to have a controlling effect against corruption is the assumption that those politicians who are willing to engage in forms of electoral corruption,8d269e8ac6ff may upon winning the election be more likely to engage in other forms of corruption in the fulfilment of their mandate. For example, a candidate who benefits from a private donation in violation of campaign finance regulations may, once they assume public office, abuse and distribute state resources to the donor.

Conversely, corrupt leaders who are already in power may seek to weaken electoral integrity so that the level of political competition is reduced. They can do this by manipulating the various phases of the electoral cycle outlined in Figure 1, for example, the manipulation of registration or political finance processes to ensure a viable political challenger cannot contest the election. In this way, these leaders may remove effectively the checks that other political parties and candidates have on their actions and continue to engage in or even scale up corruption in the future (Pring and Vrushi 2019).

Therefore, electoral integrity measures which address electoral corruption and those which protect political competition may have a preventative effect against downstream manifestations of corruption.

The next section provides an overview of studies which have tested the assumptions regarding the effect of electoral integrity on control of corruption. Due to inherent measurement challenges, the empirical evidence is more extensive for some of the assumptions in comparison to others.

Can improved electoral integrity reduce corruption?

Democracy, electoral integrity and corruption

Relatively few studies exclusively explore the relationship between corruption and electoral integrity; however, there is a vast literature on the relationship between democracy and corruption.

While some older studies found there is a negative linear relationship between democracy and corruption (Goldsmith 1999; Sandholtz and Koetzle 2000), numerous subsequent studies indicate that this relationship is not straightforward.

For example, Jetter et al. (2015) found that democracy reduces corruption, but only in countries that have passed the GDP per capita level of approximately US$2,000 (in 2005); conversely, they found that democracy increases corruption in poorer countries.

Some studies disaggregate the concept of democracy, enabling the observation of the effects of specific components, such as the estimated level of electoral integrity, on corruption. For example, Pellegata’s (2012: 6) study relied on a sample of 112 countries using data World Bank’s Control of Corruption (CC) Index as a measure of corruption. They found that controlling for the influence of other aspects of democracy, the mere existence of competitive elections helps constrain corruption (Pellegata 2012).

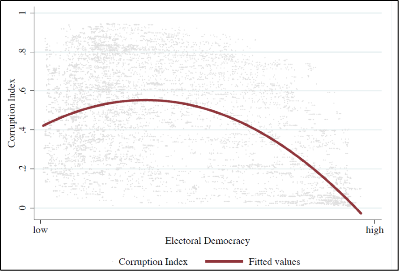

McMann et al. (2017) assessed V-Dem data for 173 countries between 1900 to 2012 to measure the relationship between corruption and what they termed “electoral democracy”658a504616ed (see Figure 2). They identified evidence of a non-linear relationship whereby countries with low levels of democracy tend to experience an initial rise in corruption when they begin to transition to higher levels of electoral democracy; however, after reaching a certain threshold, increasing levels of democracy begin to translate into lower corruption levels more consistently.

Figure 2. The relationship between corruption and electoral democracy

Source: McMann et al. 2017: 14

McMann et al. (2017) found when a country introduces or reintroduces elections (of any quality) into its system, it tends to first increase corruption, but as the quality of election improves, corruption decreases. They hypothesised that the mere introduction of elections, regardless of how free and fair they are, incentivises elites in authoritarian systems to transfer “public funds and other state resources and grant favours to those whose loyalty they need” in order to retain their position of power in a democratising system (McMann et al. 2017: 8).

Electoral accountability

McMann et al. (2017: 9) further interpreted their findings with reference to the electoral accountability theory, namely that in free, fair and competitive elections, voters are better equipped to hold incumbent politicians accountable for their actions than in manipulated elections (McMann et al. 2017: 9).

Some other studies also lend credence to this theory. For example, Winters and Weitz-Shapiro (2013) carried out an experiment as part of a nationwide survey held in Brazil, finding that that the vast majority of voters demonstrate a willingness to punish politicians suspected of corruption, independent of their views on other aspects of the performance of the politicians. However, other studies have identified empirical deviations from the theory of electoral accountability, including in developing countries with weak institutions, but also countries with well-established democracies (De Vries and Solaz 2017).

Different variables account for these deviations depending on the context. These include the significance of in-group and partisan loyalties (Anduiza et al. 2013; Solaz et al. 2017). For example, Anduiza et al. (2013) carried out a survey experiment in Spain, finding that voters react differently depending on whether the politician implicated in corruption is a member of a party they support or not.

Voters may also be dissuaded by sanctioning corrupt officials if they are likely to receive benefits from them (Manzetti and Wilson 2007; Fernandez-Vazquez et al. 2016), For example, Manzetti and Wilson (2007: 963) found that corrupt governments can keep voters’ support by manipulating government institutions to benefit their clientelist networks. They test their argument on a cross-national sample of citizens in 14 countries (Manzetti and Wilson 2007). Boas et al. carred out an experimental study in Brazil, finding that while voters tended to sanction corrupt incumbent mayors in a hypothetical scenario, this did not hold when the same scenario was presented for their local incumbent mayors. According to their interpretation, in the hypothetical scenario voters are guided by prevailing norms against corruption in Brazil, but the field experiment demonstrates such norms may give way to other concerns such as employment and health service benefits when they actually cast their vote.

Further, Jucá et al. (2016) found that higher levels of campaign spending reduced the effect of electoral punishment of incumbents (lower-house members of congress) who engaged in malfeasance scandals in Brazil. Namely, above a certain threshold of funding, Brazilian members of congress were less likely to be affected by publicised corruption scandals due to their greater ability to invest in their campaigns (Jucá et al. 2016).

Other studies point to the explanatory value of contextual factors such as economic growth (Klašnja and Tucker 2013; Zechmeister and Zizumbo-Colunga 2013). For example, Klašnja and Tucker (2013) utilised survey experiments in Sweden and Moldova, finding that in a low corruption country such as Sweden, voters tend to react negatively to corruption regardless of the state of the economy. However, in a high corruption country such as Moldova, voters negatively react to corruption only when economy is doing badly.

Other studies focus on the motives and behaviour of politicians rather than voters. Ferraz and Finan (2011) used data from audit reports of local administrations’ federal funds spending in Brazil to construct a political corruption measure.3487e4fe9007 They found that municipalities where mayors face re-election incentives have significantly lower corruption levels than those with second-term mayors facing binding term limits (Ferraz and Finan 2011: 1307). They also found that this result was stronger in municipalities where the probability of detecting corrupt practices is higher, as measured by the presence of local media and judiciary agents.

Controlling downstream corruption

One of the assumptions predicting that electoral integrity leads to a greater control of corruption is that certain electoral integrity interventions can be effective in preventing the manifestation of downstream forms of corruption. There has been comparatively less literature testing this kind of assumption, which may be explained by the inherent difficulty of quantifying levels of downstream corruption.

Nevertheless, several studies consider if forms of electoral corruption may lead to further corruption. Rueda and Ruiz (2020) analysed the behaviour of elected officials following elections with compromised integrity, relying on a quasi-experimental design and data from Colombian regional elections. They identified a positive causal effect of vote-buying on the likelihood of an election winner being prosecuted for violations of disciplinary code of public officials (Rueda and Ruiz 2020). In other words, if politicians who engage in vote buying are more likely to engage in corruption or other misconduct once in office, it suggests an electoral integrity measure effectively targeting vote buying may have a controlling effect on downstream manifestations of corruption.

The role of political finance – such as campaign donations – can be especially relevant. Figueroa (2021) used data on bribe collections by high-level bureaucrats and the delivery of bribes to political figures in Argentina, finding that corruption is motivated by the incumbents’ needs to finance elections, as more bribes were delivered shortly before elections (although they noted some of this may be attributable to personal enrichment rather than political finance purposes).

Lo Bue et al. (2021) analysed V-Dem data for 161 countries from 1900 to 2017 and found that political clientelism, measured by “whether vote buying exists, and whether political parties offer material goods to their constituents in exchange for political support” was associated with higher levels of political corruption.

Gulzar et. al (2022) analysed comparative municipal-level data from Colombia and found that those municipalities with weaker limits on political contributions tended to have a higher “number and value of public contracts assigned to the winning candidate’s donors”. Holland and Freeman (2021) similarly found that politicians in Colombia were more likely to award public infrastructure contracts to individuals and entities who had supported them with donations. Kalla and Broockman (2016) used a field experiment to demonstrate that having made a political contribution increased the likelihood of securing a meeting with influential policymakers in the US. This all, again, serves to suggest that electoral integrity interventions that focus on political finance may stem the emergence of future forms of corruption, especially undue influence and clientelism.

Other studies compare levels of political competition, which can be undermined by weak electoral integrity, with estimated levels of corruption. Schleiter and Voznaya (2012) through a comparative analysis of corruption in 70 democracies find evidence for their hypothesis that in settings in which “the competitiveness of a party system helps to make information and effective choices available to the electorate”, informed voters will “select politicians who are likely to curb corruption and hold accountable those who do not”.

Furthermore, Johnston (2017) argues that since high-quality and well-institutionalised political competition means that political power is won or lost in a publicly visible process, parties will be incentivised to respond to voter’s preferences, including by undertaking “credible action” against corruption. Johnston (2017) compared the TI Corruption Perceptions Index with an index of political competitiveness called PARCOMP, controlling for GDP per capita and the level of institutionalisation of the political competition. They found that the well-established link between higher GDP per capita and lower levels of corruption becomes stronger when countries have well institutionalised and competitive party systems.

The type of electoral system

Studies suggest that different electoral rules and systems may have varying effects on corruption (see De Vries and Solaz 2017; Rose-Ackerman 1999; Kunicová and Rose-Ackerman 2005; Kunicová 2006; Birch 2007; Golden and Mahdavi 2015; Norris 2017; Ruiz-Rufino 2018).

Some of these studies suggest that majoritarian electoral systems are associated with lower levels of corruption in comparison with proportional ones (Persson et al. 2003; Kunicová and Rose-Ackerman 2005; Rudolph and Daubler 2016). For example, Kunicová and Rose-Ackerman (2005: 597) found that proportional representation (PR) systems are more vulnerable to political rent-seeking than plurality systems, suggesting that the greater number of viable candidates enabled by the former system can challenges for voter in monitoring corruption.

However, other research has found that majoritarian systems are associated with more forms of electoral corruption compared to proportional representation systems. Birch (2007) carried out a cross-country study of 24 post-communist countries between 1995 and 2004 and found that electoral fraud is more likely in elections held in single-member districts (SMD) under plurality and majority rule than in those under PR. Birch (2007) provided two reasons for this finding. First, candidates in SMD have more to gain with manipulating elections than those in PR systems (Birch 2007). Second, malpractice is more efficient in SMD systems as the number of votes needed to be altered for the win is lower than in PR systems (Birch 2007).

Furthermore, there is evidence single-member plurality districts incentivise parties and candidates to engage in malpractices like vote-buying and partisan gerrymandering (Norris 2017; Ruiz-Rufino 2018). Ruiz-Rufino’s (2018: 332) study relied on data from 323 parliamentary elections in 59 new or developing democracies between 1960 and 2006. They found that when electoral contests are expected to be close, majoritarian institutions incentivise incumbents’ electoral misconduct more than proportional representation institutions. However, they found this effect becomes less significant where countries have a long historical record of holding clean elections and where there are credible and robust EMBs that can prevent the use of electoral malpractices (Ruiz-Rufino 2018: 333; see also Mozaffar and Schedler 2002; Birch 2007).

The role of electoral integrity in constraining specific forms of corruption

Aggregate corruption measures

The cross-country studies described in previous sections tend to rely on expert and survey based measures of corruption, which aim to tap into different forms of corruption, ranging from petty to grand (e.g. Pellegata 2012; McMann et al. 2017; Hummel et al. 2019). For example, the aforementioned study by McMann et al. (2017), which found that improving the quality of elections reduces corruption, relied on the V-Dem measure of corruption which is based on expert perceptions. The V-Dem corruption index is composed of six indicators, including executive bribery, executive embezzlement, public sector bribery, public sector embezzlement, and legislative and judicial corruption. This measure aims to capture different types of corruption: petty and grand, bribery and theft, and corruption aiming to influence law-making and affecting law-implementation (Coppedge et al. 2021: 296).

However, in some studies corruption as the dependent variable has been disaggregated further into its different forms. For example, Hummel et al. (2019) used disaggregated measures of corruption from the V-Dem project and tested the effects of political finance reforms on four types of corruption: executive (average of executive bribery and executive embezzlement indicators), public sector (average of public sector bribery and public sector embezzlement), legislative and judicial. They found that political finance subsidies reduce executive, public sector and judicial corruption which suggests the relevance of political finance reforms for controlling corruption, including at high levels of political power.

Other studies considering disaggregated forms of corruption coalesce around manifestations of so-called political corruption and administrative or petty corruption.

Political corruption and grand corruption

Political corruption is typically defined by the actors involved, which are persons occupying top-level positions in the political system, and the purpose of the corrupt behaviour, which is to remain in power (Amundsen 2006). This encapsulates forms of electoral corruption, such as vote-buying, and other corruption offences such as undue influence and cronyism. Unsurprisingly, a large share of studies on the relationship between electoral integrity and corruption focus on political corruption because the criticality of political actors is common to both. These studies typically use observational data to construct corruption measures, such as audit reports of federal spending in Brazil (Ferraz and Finan 2011), leaked records of bribe taking and giving in Argentina (Figueroa 2021), financial disclosure records in Russia (Szakonyi 2021) and publicised corruption scandals in Brazil (Jucá et al. 2016).

For example, Vaz Mondo (2016) constructed a measure of political corruption81262d975d2b based on results of a randomised federal audit programme in Brazilian municipalities and irregularities identified related to procurement fraud, diversion of public funds and over-invoicing for goods and services. They argue that electoral accountability7ce6abf75769 may serve as a deterrent to political corruption, after finding evidence that future levels of corruption will be lower in those municipalities where the previous mayor or administration involved in corruption was voted out of office.

Similarly, Ferraz and Finan (2011) constructed a political corruption measure based on audit reports of local administrations’ spending of federal funds, which was intended to capture fraud related to public procurement irregularities, diversion of public funds and over-invoicing of goods and services. They found that voters were more likely to punish those incumbents based in municipalities with higher political corruption levels and the effect was increased in municipalities with a greater presence of local media.

Mietzer’s (2016: 100-101) in-depth case study of Indonesia described that while political finance regulations were introduced in the mid-2000s to reduce public party funding and increase private donations, in reality they led to fewer officially registered private donations, suggesting a shift to off-book donations (Mietzer 2016: 96). Furthermore, following the reduction in public funding, the central party turned to oligarchs for support. The political finance system allowed party leaders to channel unlimited amounts of funds into their parties under the category of ‘membership dues’ (Mietzer 2016: 96), which in turn enabled oligarchs to fund parties without being subjected to contribution caps, thus creating risks of undue influence on the policymaking process (Mietzer 2016: 96). They argued this demonstrated the importance of carefully designing effective political finance regulatory regimes to prevent undue influence, cronyism and political corruption.

Further, Bauhr and Charron (2018) note a distinction between public scandals implicating political figures of which voters become directly aware and grand corruption schemes in which ‘transactions which are rarely directly observed by the general public’. Analysing 21 European countries, they found national estimates of grand corruption levels were negatively associated with voters’ propensity to punish corrupt incumbents; namely in settings with high levels of grand corruption, voters tend to be more loyal to corrupt politicians (for example, due to fear of losing out on benefits distributed via patronage networks) or are more likely to become disillusioned and refrain from voting. While not directly explored by the authors, this suggests that the causal effects of electoral integrity in controlling grand corruption which occurs ‘out of sight’ may be less clearcut than for forms of corruption which more visibly involve political actors.

Administrative corruption and petty corruption

Political corruption is typically distinguished from administrative corruption, which, for example, may manifest in the delivery of public services where the main perpetrators are civil servants rather than political figures. As Vries and Solaz (2017) argue that when voters directly experience administrative corruption – for example, police demanding a bribe – they may not attribute it back to the political figures who enable it. This raises the possibility that electoral integrity may have a less direct causal effect on controlling such forms of administrative, street-level corruption.

Bourassa et al. (2022) explored this question using a sample of 60 countries from Africa and Latin America. They found that direct experience of corruption at the hands of ‘street-level bureaucrats’ made voters more likely to punish incumbent political figures (Bourassa et al. 2022). This even holds in settings where voters believe political figures have less control over street-level bureaucrats. This suggests that administrative corruption can in fact serve as a driver of anti-incumbency voting as a means of holding elected officials to account for poor governance. However, another study focusing on Europe found that personal experience with administrative corruption did not have a significant effect on voting behaviour (Bauhr and Charron 2018: 438).

In a case study of Turkey, Kimya (2017) demonstrates that, while the AKP was relatively successful in tackling petty corruption (analogous to administrative corruption due to the focus on street-level bureaucrats), it failed to better regulate political party and campaign finance, thereby opening the door for cronyism.

Overall, the direct effects of electoral integrity on administrative or petty corruption remain understudied. Bauhr et al. (2019) explored the effects of women’s political representation on both petty and grand forms of corruption, as estimated by regional-level, non-perception-based measures. They found that an increase in representation of women in local councils is associated with a decrease in both forms of corruption. A later study by the authors (Bauhr and Charron 2021) found that this effect may be weakened over time. Moreover, a recent study by Bauhr et al. (2024) suggests that women elected representatives in regional level parliaments reduce street-level bribery, measured as citizens’ self-reported experience of bribery, particularly in contexts where relatively few women are elected. While the focus of these studies was on women’s political representation, rather than electoral integrity, it demonstrates the potential for future studies exploring the effect of governance variables on disaggregated forms of corruption.

Key electoral integrity measures for controlling corruption

A growing number of studies in recent years have begun to focus on the role of specific electoral integrity measures on controlling corruption, with a particular focus on political finance controls (for example, contribution limits and subsidies), finance transparency, the quality of electoral management and media environment.

Political finance measures

One of the main political finance regulatory instruments are contribution limits (or donation caps), which restrict how much third-party funding political parties or campaign candidates can receive. Nevertheless, their utility in countering corruption is disputed. Ben-Bassat and Dahan (2015) found that political finance contribution limits increase corruption perceptions levels; they suggest that introducing contribution limits may increase the demand for illegal contributions and consequently increase corruption levels. Using state-level data from 1990 to 2012 from the US, Hand (2018) found there was no significant relationship between limits and corruption. France (2023) concurs that the evidence on the effectiveness of contribution limits in addressing corruption is limited, but notes that existing studies point to the importance of having a robust compliance framework to enforce contribution limits.

Another instrument comes in the form of subsidies which aim to reduce the level of private sector influence in the electoral landscape by allocating public funding to political parties and candidates, often proportionally according to votes. A number of studies have found that the effect of political finance subsidies on estimated corruption levels may be negligible (Evertsson 2013; Norris and Abel van Es 2016). Some case studies indicate that where subsidies are poorly managed, they may even serve to enrich corrupt elites (Calland 2016; Mietzer 2016).

However, Hummel et al. (2019) argued that a more comprehensive approach to this topic is merited because existing studies either focus on single cases or use a time-limited cross-sectional approach. Their study relied on an original dataset measuring political subsidies in 175 countries between 1900-2015 and disaggregated corruption measures from the V-Dem project (Hummel et al. 2019). The concept of political finance in their study encompasses three elements: the regulation of money in politics, government subsidies to support contestants for public office and enforcement mechanisms (Hummel et al. 2019: 3).

They concluded that political finance subsidies reduce corruption “by reducing private money’s importance in politics and increasing sanctions for corrupt behavior”. These findings remain stable after controlling for GDP per capita, GDP growth and the quality of democracy (Hummel et al. 2019: 18).

Campaign finance reforms in Paraguay

Hummel et al. (2019) illustrate the role of political finance reforms in constraining corruption in Paraguay, which introduced political finance legislation following the 1993 elections. As they note, this law outlawed the use of state resources for campaign purposes and required political parties to publish financial reports. In addition, it introduced subsidies for campaigns and yearly subsidies for political parties (Hummel et al. 2019: 9).

They found the evidence suggests that the law introduced clarity in terms of what is legal and illegal in political finance and established an enforcement regime. According to interviewees, after only one electoral cycle following the adoption of these reforms, misuse of state resource and embezzlement dramatically dropped (Hummel et al. 2019: 10-11). Further, the introduction of public subsidies reduced (though did not eliminate) incentives for corruption as it decreased the need to take donations from less scrupulous sources (Hummel et al. 2019: 11).

Another integral measure of political finance relates to financial disclosure. Djankov et al. (2009), in a study of 175 countries, found that the existence of laws requiring public disclosure of political finance is positively associated with government quality, including lower corruption.

Szakonyi (2021) analysed the role of financial disclosure requirements in political selection in municipal council elections in Russia, relying on an original dataset of 446,503 candidates to 25,724 municipal council elections between 2009 and 2017. They argue that financial disclosures function as a personal audit, enabling journalists and prosecutors to investigate the illicit enrichments of politicians which should deter them from running for office. They found that the introduction of financial disclosure requirements led to a 25% decrease in the share of incumbents seeking re-election and a 10% decrease in the share of candidates with suspicious financial histories.

Electoral management bodies (EMBs)

EMBs are key institutional component of electoral integrity (van Ham and Lindberg 2015; van Ham and Garnett 2019; Norris 2023).

A recent study by Lundstedt and Edgell (2020), relying on V-Dem data for 160 countries from 1900 to 2016, considered the relationship between EMBs and clientelism. To construct the measure of clientelism, the authors used the V-Dem clientelism index, which is composed of three underlying indicators: the extent of vote and turnout-buying, clientelist party-voter linkages, and particularistic government spending (Lundstedt and Edgell 2020: 11). They found that capacity of EMBsa22e2a0cbe70 increases, clientelism decreases. Lundstedt and Edgell explain the results by arguing an increase in EMB capacity undermines so-called broker monitoring capacity1794fd5bc7e7 and increases voter moral hazard,79c6f00b6eb3 which ultimately makes clientelism more costly for political parties.

Nevertheless, there are important nuances to consider with regards to EMBs. As Norris (2023: 95) points out, there is a debate in the literature whether it is more effective to have EMBs independent of all parties or to engage representatives from all the main political parties in the decision-making process (López-Pintor 2000; Wall et al. 2006; Aaken 2009; Ugues 2014). Moreover, recent research questioned the effectiveness of EMBs in non-democratic settings. In a case study of Thailand, Desatova and Alexander (2021) argue that in non-democratic settings characterised with high political polarisation and entrenched elites, EMBs risk being co-opted to serve the interests of the incumbent.

Some research has suggested that international election observers can play a role in reducing electoral corruption. Namely, Hyde’s (2007) study, focusing on Armenia’s presidential elections in 2003, finds that while observers may not eliminate election fraud, they can reduce fraud on election day in the polling stations they visit. However, other cross-country studies find no effects of election aid and observers on election quality (Norris 2015).

Open media environment

The media environment is frequently cited in the literature as an important oversight mechanism for detecting corrupt practices. De Vries and Solaz (2017) found that whether or not voters ‘punish’ corrupt politicians by withholding their vote for their re-election depends, in addition to factors such as local social norms, on the absence of a fair and open media landscape. Anduiza et al. (2013) found that increased “political awareness” leads to a decrease in the forms of partisan bias that can lead voters to refrain from sanctioning corrupt politicians.

The study by Ferraz and Finan (2011: 1307), described in the previous section, found that the effect of electoral accountability on reducing political corruption is stronger in those municipalities where the probability of detecting corrupt practices is higher, as measured by the presence of local media and local judiciary agents. Free press was also found to be an oversight mechanism capable of bringing malpractices to light in the study by Birch and van Ham (2017).

Media environment in Madagascar

In a case study of Madagascar, Birch and van Ham (2017) highlighted the role the media environment played in covering and publicising electoral misconduct, which consequently helped mobilise calls for electoral reform. A study from Moser (2008) similarly demonstrated that access to radio and television stations in Madagascar made voters more likely to resist attempts of vote-buying.

Szakonyi’s (2021) study on political finance reforms and political selection in Russia, also found that the financial disclosure laws will result in a greater turnover of incumbents and deter candidates with suspicious financial histories from running in municipalities where there is a strong independent media presence.

A study from Larreguy et al. (2014) on political accountability in Mexico found that voters are likely to punish malfeasant mayors, but only in those electoral precincts which are covered by local media stations. Specifically, they found that the presence of each local radio or television station is associated with a reduction of the vote share of an incumbent political party alleged to be corrupt (Larreguy et al. 2014).

Lastly, evidence suggests investment in the media environment can pay high dividends. Jackson and Uberti (2018) assessed official development assistance (ODA) spending against V-Dem electoral integrity estimates and found that donor-led interventions taking place during the election year can be particularly effective in terms of promoting a more balanced media landscape, as measured by the number of parties and individuals able to run paid campaign advertisements on national broadcast media channels.

- For an overview of the limitations of different data sources see: Van Ham 2015; Garnett and James 2020.

- Birch (2009) argues the defining characteristic of electoral corruption “is that it involves the abuse of electoral institutions for personal or political gain”. Expanding on this, Bosso and Albisu Ardigó (2014) argue that electoral corruption occurs primarily in three ways: vote-buying, abuse of state resources and election rigging.

- Electoral democracy takes into account the extent of freedom of association, suffrage, clean elections, the election of the executive and freedom of expression, relying on the Varieties of Democracy’s Project (V-Dem) data (McMann et al. 2017: 25; Coppedge et al. 2021: 43).

- Ferraz and Finan (2011) consider political corruption to be any irregularity associated with: i) fraud in the procurement of public goods and services; ii) diversion of public funds for private gain; and iii) over-invoicing of goods and services (Ferraz and Finan 2011: 1283). As a result, the principal measure of corruption is the total amount of resources lost to corrupt activities (Ferraz and Finan 2011: 1283).

- Understood as behavior by public-decision makers where preferential treatment is given to individuals and narrow interests are favoured at the expense of public interest (see Lambsdorff 2007).

- This study considered the following conditions for the occurrence of electoral accountability: i) there was at least one election for municipal office between audits; and ii) the mayor in power during audit 1 ran for re-election (Vaz Mondo 2016). When the second condition did not hold, Vaz Mondo (2016) looked at whether either a candidate from the same party, from a coalition party, a relative of the mayor or a member of the administration was presented as a candidate for succession.

- The authors used the V-Dem Project’s data to measure EMB capacity, which is based on a question: ‘Does the election management body (EMB) have sufficient staff and resources to administer a well-run national election?’ For details, see: Lundstedt and Edgell (2020: 13).

- As the capacity of EMBs improve, Lundstedt and Edgell (2020: 10) argue that brokers who are tasked with persuading or threatening voters with resources, require costlier and more sophisticated methods to monitor voters’ compliance, or need to switch their focus from swing to loyal voters.

- As the capacity of EMBs improve, and consequently, broker monitoring capacity decreases, voters have less to fear from individual sanctions for not voting as agreed. Lundstedt and Edgell (2020: 10) argue that this will increase incentives for voters to accept clientelist benefits without fulfilling their end of the bargain.