Query

Please provide an overview of the gendered impacts of corruption and women’s role in preventing corruption.

Caveat

Corruption has a vast and complex range of effects on women across different sectors, locations, age brackets, and other variables. As such, a comprehensive assessment of the impact of corruption on women and their potential anti-corruption roles is beyond the scope of this Helpdesk Answer.

Instead, the paper limits itself to consideration of the gendered impact of corruption in four important areas explicitly mentioned in a recent resolution of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption entitled Addressing the Societal Impacts of Corruption (2023):

- access to quality and affordable health services

- sexual forms of corruption

- equitable access to justice

- meaningful participation in decision-making processes and public life

In addition, this Helpdesk Answer recognises the contribution of the comprehensive 2020 UNODC study, Time is Now: Addressing the Gender Dimensions of Corruption. As such, it prioritises an assessment of the literature published since 2020 in those four areas, to avoid duplicating existing material.

The Helpdesk Answer draws on previous publications by the same author (Bullock and Jenkins 2020; McDonald and Jenkins 2021).

Impact of corruption on girls’ and women’s ability to access quality and affordable health services

Impact of corruption on women’s access to health services

Women’s contact and bribery rates with health services

Gender role socialisation and societal norms matter in terms of women’s lived experience of corruption when accessing health services. Due to stereotypical gender roles, on average women assume greater responsibility as primary caregivers for children and the elderly (Eagly and Wood 2016). In addition, due to gender specific needs, especially during their reproductive years, and the fact that some health concerns disproportionately or exclusively affect women (Habib et al 2021), they may interact with health-care providers more often than men do (Devrim 2021; Nawaz and Chêne 2009; Sen et al. 2007).One study in Nicaragua found that women constitute nearly two-thirds of all patients in the public health facilities (Transparency International 2014). As a result of their socio-economic status and position as caregivers, women tend to interact more with and rely more on public health services (UNODC 2020: 20).

Due to this higher contact rate with health services – and the range of social norms and biological factors behind it – women may be more exposed than men to corruption in health care (Bauhr and Charron 2020; Transparency International 2010). Survey data from a regional household survey across Latin America and the Caribbean indicates that women are more likely than men to pay bribes to access health services (Transparency International 2019a). Similarly, a national level survey in Peru found that while in general women paid fewer bribes than men, this was not the case in the health sector, where women were more likely to report having paid a bribe (Proetica 2017). More recent research in the Democratic Republic of Congo found that women were more likely than men (42% to 36%) to state that the chance of encountering corruption when accessing health services was “very high” (Bergin 2024: 44-47).

Complicating this picture, data from the 9th round of the Afrobarometer surveys (2024) found that across the 39 countries covered, women were slightly less likely to report paying a bribe to access medical care than men (19.9% to 21.8%). Ouedraogo et al. (2024) drew on data from the 8th survey round of the Afrobarometer to investigate the relationship between reported bribe-paying in the health sector and access to health services. They found that differences between men and women were minimal: corruption in the health sector is associated with a lack of access to care for both men and women. In fact, women in subnational regions with a high incidence of bribery in the health sector were marginally less likely than men to report they had gone without access to health care on multiple occasions26ca599a54db (Ouedraogo et al. 2024).

Another study on the gendered impact of corruption in Albania found that while men and women were equally liable to be requested to pay a bribe to access health services, these requests can be more detrimental to women and especially to single mothers, as the gender wage gap and lack of adequate childcare services means they are generally poorer than men (Devrim 2021: 25). Moreover, it should be noted that it is primarily women who shoulder the burden of unpaid care work when their families are unable to access health care (Transparency International Zimbabwe 2020: 29).

Gender-specific corruption risks in health services

Beyond simply the reported rate of bribe-paying to access health services, there is some evidence that women may be at particular risk when other forms of corruption become endemic in health-care systems, due to underlying socio-economic inequalities and gendered power dynamics (Devrim 2021).

At the point of service delivery, Sen et al. (2007) observe that women who are hospitalised or in a precarious physical state struggle more than men to object to predatory corrupt practices such as over-invoicing. A recent study from Madagascar, for instance, found a high risk of women being overcharged by health-care providers for contraceptive pills and implants when consulting family-planning services (Bergin 2024: 31). This aligns with previous studies that found that service users in clinics in Kenya were charged higher fees than the official prices for oral conceptive pills (Tumlinson et al. 2013). Information asymmetries between women patients and health providers regarding the necessity of certain procedures and the associated costs can heighten the risk of this kind of corruption at the point of service delivery (Camacho 2023; Devrim 2021: 10). Certain population groups, such as older women, women living in rural areas or women with disabilities might be particularly affected by discriminatory attitudes towards gender roles and lack of information (Devrim 2021: 18).

Moreover, certain types of specialised care present specific risks, including in relation to women’s sexual and reproductive health. A recent literature review concluded that corruption diverts funds from obstetric health care and worsens the quality of maternal and perinatal services (Camacho 2023). A large-scale survey of over 4,500 people conducted in Madagascar identified maternal delivery as being a high-risk area for corruption, in the form of illicit fees demanded by midwives and unnecessary caesarean procedures (Bergin 2024: 31). There is also evidence, including from Hungary and Albania, of women who have just given birth being forced to pay a bribe to see their baby or to ensure that a physician was present during childbirth (Devrim 2021: 26-27; Kremmer 2020: 26; Rheinbay and Chêne 2016). A study by Stepurko et al. (2015) suggested that at that time in Ukraine, 50% of women giving birth in institutional facilities reported making informal payments to health-care workers. A study by the Kenyan Federation of Women Lawyers (2007) found that women unable to pay unofficial fees for family-planning methods were often ignored completely by medical staff.

Moreover, these kinds of informal payments can deter low-income mothers from giving birth in hospitals, thereby endangering lives (Camacho 2023). In Kenya, for instance, fees and the requirement for mothers to purchase basic materials such as gloves and disinfectants for use during childbirth meant that women unable to afford these items were at higher risk (Pandolfelli and Shandra 2013; Sommer 2019). Perhaps unsurprisingly, several quantitative studies have pointed to a correlation between corruption and the infant and maternal mortality rate (Muldoon et al. 2011; Pinzón-Flórez et al. 2015; Ruiz-Cantero 2019).

Meanwhile, unnecessary procedures, particularly caesarean sections, can present lucrative opportunities for health-care providers and may also be used to speed up births in understaffed clinics (a problem to which corruption may contribute) (Camacho 2023). A linear multivariate regression model developed by Ortega et al (2020) suggested that an annual 1 percentage point increase in the ratio of illicit financial flows to total trade was associated with a 0.46% decrease in the level of family planning coverage and a 0.31% decline in the percentage of women receiving antenatal care (Ortega et al. 2020).

Family planning and abortion-related care can involve sensitive or stigmatised areas with large power differentials between patient and health worker. This, combined with socio-economic disadvantages faced by women, can heighten the risk of extortive forms of corruption and make it harder for them to report instances of corruption and access justice (McGranahan et al. 2021). Schoeberlein (2021) presents a more detailed overview of how corruption undermines women’s sexual and reproductive health rights.

The targeting of health care provision and registration of intended beneficiaries can be distorted by corruption, as was reportedly the case in Rwanda, where single mothers who were removed from a social protection programme providing health care alleged that other people had bribed local authorities to be added to the list in their place (Bergin 2024: 47).

As such, the most noticeable effects of corruption on women typically occur at the point of service delivery, where service providers and users interact, and demands for bribes or illicit extra fees are made. Nonetheless, less visible forms of corruption can have equally pernicious effects on women’s access to health services.

The health sector is characterised by large flows of money, information asymmetries, specialised equipment, complex organisational structures and the dependency of often-vulnerable target population groups (Abisu Ardigó, and Chêne 2017; Cooper et al. 2019; Hutchinson et al. 2019; Schoeberlein 2021). These factors create opportunities for the corrupt abuse of power in the management of resources such as personnel, goods, supplies and budgets.

Corruption by senior public officials can take the form of undue influence that distorts health-care policy and the allocation of available resources, as well as large-scale embezzlement that diverts funds and exacerbates shortages of medical infrastructure, supplies and personnel (Hsiao et al. 2019; Onwujekwe et al. 2018). In countries with a high incidence of corruption, total investment in health care is generally lower (Schoeberlein 2021: 8). In these settings, those public resources that are made available for the health sector are typically allocated to large-scale prestigious projects, such as new hospitals and expensive equipment, that are conducive to illicitly siphoning off funds, while smaller-scale and geographically dispersed services, such as local family planning centres and sexual health clinics remain underfunded (Onwujekwe et al. 2018: 13).

Even after budgetary funds have been earmarked for health services and received by health-care facilities, various forms of corruption can reduce the quality and quantity of health-care provision, including nepotism in the recruitment of health-care workers, kickbacks during procurement, ghost workers, and fraud (Abisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017; Cooper 2019). As such, corruption across the health sector value chain can lead to long waiting times, poor quality of service, insufficient access to medicine, and other problems that could mean life or death (World Bank Group 2015).

There is some evidence that the impact of these forms of corruption disproportionately affect women, who Nawaz and Chêne (2009) characterise as the "shock absorbers" of public officials' corruption in the health sector. This is for two reasons.

First, in many cases it is the unpaid care work undertaken by women that fills any gaps in health-care provision created by corruption (Transparency International Zimbabwe 2020: 29).

Second, while there is limited empirical evidence as yet, Devrim (2021: 15) suggests that where large-scale corruption reduces the available budget, women’s health services could be especially vulnerable to budget cuts, particularly in areas where women are underrepresented politically (Bullock and Jenkins 2020). It does appear that women’s health supplies and pharmaceuticals are more likely to be over-invoiced or “lost” due to corruption in procurement; Goetz and Jenkins (2004) posit that this is because women as a collective bargaining group are thought by those in power to lack the political clout to object to corrupt practices. Such neglect can have life-threatening consequences for women in desperate need of this medicine and equipment (Sen et al. 2007; UNDP 2010).

Mpambije(2017) and Camacho (2023) both provide numerous examples of cases in which corrupt schemes deprived maternal and perinatal health services of funding and resulted in worse health-care outcomes for women and children.

Sexual corruption in health care

While little specific scholarship exists on sexual corruption in the health sector, there is some evidence that the phenomenon is widespread (Coleman et al. 2024). Data from the Global Corruption Barometer shows that in Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, one in five people has experienced or knows someone who has experienced sexual corruption when accessing government services such as health care or education (Transparency International 2019b). While men and boys may also be exposed to forms of sexual corruption, women are reportedly more likely to be targeted (Cooper and Cushing 2020). A survey in Latin America, for instance, found that women are more likely to express the view that sexual corruption occurs at least occasionally (Transparency International 2019c). Partly, this is due to material gender inequities; the fact that women generally possess fewer – or have less control over – financial assets can leave them less able to pay material bribes,3259ed6c2de2 which may lead to corrupt individuals abusing their positions of authority to coerce and exploit women into sexual activities in lieu of cash or other material goods (Transparency International 2020a). Where sexual corruption in the health sector becomes common knowledge among service users, it is likely to undermine progress towards universal health coverage by deterring women and girls from accessing health care when they need it (Coleman et al. 2024).

Sexual corruption in the sector affects health workers as well as service users. Recent studies in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar and the UK have all documented multiple instances in which male supervisors solicit sex from female medical trainees in exchange for jobs and good grades (McDonald and Jenkins 2021; 30-31; Bergin 2024: 45; Gallagher et al 2023). Kirya (2019) has also documented how sexual corruption, particularly targeting female nurses, relates to recruitment and promotion practices.

Role played by women in preventing corruption in the health sector

There is little scholarship exploring the potential role women can play in curbing corruption in the health sector specifically. Nonetheless, some authors have suggested that due to their frequent social role as caregivers, women have a particular interest in efficient public service delivery and a well-functioning and corruption-free state that can deliver public goods in the area of social welfare (Wangnerud 2015). Some randomised control trials have indicated that women are less likely than men to misuse social welfare resources (J-PAL 2015). Given that women account for nearly 70% of the global health workforce (Cooper and Cushing 2020: 15),their potential role in addressing corrupt practices in the health sector could be subject to further study. Such work would need to account for the fact that in many countries, men continue to be overrepresented in senior positions, while women constitute the large majority of nurses and administrators in the sector (Devrim 2021: 11).

Other authors have proposed strengthening the role of women in demand-side strategies to curb corruption in health services, including through public hearings, community monitoring and other social accountability tools that amplify the voices of disadvantaged groups such as poor women (Naher et al. 2020). Encouragingly, a recent study that conducted focus groups with adolescent girls and young women living in slums in Uganda found that many of them thought that reducing corruption would noticeably improve the delivery of sexual and reproductive health services (McGranahan et al. 2021).

Sexual corruption

Impact of sexual corruption on women

In the last decade, increasing scholarly and policy attention has been paid to forms of corruption that do not (solely) involve the exchange of money or physical goods. Prominent in this discussion has been the extortion of sexual acts by those in positions of authority as part of some quid pro quo transaction. This phenomenon has been referred to as ‘sextortion’5b3b3fa6e6a9 by the International Association of Women Judges (2012), which identified it as comprising three constituent elements.

First, there is an implicit or explicit request to engage in any kind of unwanted sexual activity. Second, the person who demands or accepts the sexual activity must occupy a position of authority, which they abuse by seeking to exact, or by accepting, a sexual act in exchange for exercising the power entrusted to them. Third, there is a quid-pro-quo, whereby the perpetrator demands or accepts a sexual act in exchange for a benefit that they are empowered to withhold or confer.

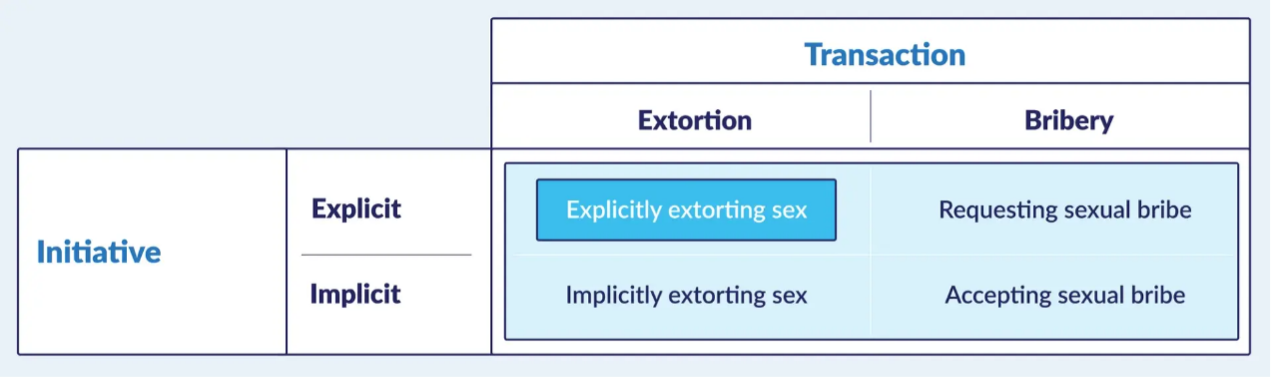

Recent work by Bjarnegård et al. (2024a) has sought to broaden the understanding of sexual corruption beyond a narrower view of ‘sextortion’, in which people in positions of authority extort sexual acts in return for goods or services to which the targeted person is entitled. In their view, in addition to this “oppressive” form of sexual corruption, there are also “opportunistic” instances of sexual corruption, whereby people with entrusted authority request or accept sexual acts in exchange for providing unwarranted privileges.

Figure 1: Abuse of authority in sexual corruption

Thus, while the traditional definition of sextortion did not encompass “sexual bribes” initiated by those looking to attain an advantage, the broader conceptualisation advanced by Bjarnegård et al. (2024: 9) does include such scenarios. The authors are, nonetheless, at pains to point out that while the person in the position of authority might not always be the one to initiate, propose or solicit sexual acts as part of a quid pro quo, the responsibility always lies with them for the abuse of power. The authors’ proposed definition of sexual corruption is thus framed to focus on the person with entrusted authority rather than the other party: “sexual corruption occurs when a person abuses their entrusted authority to obtain a sexual favour in exchange for a service or benefit that is connected to the entrusted authority” (Bjarnegård et al. 2024b).

For many years, sexual corruption remained a largely invisible phenomenon (Eldén et al. 2020: 43). More recently, tentative attempts to gauge the scale of sexual corruption have been undertaken, which have revealed it to be widespread all over the world (Eldén et al. 2020: 108). The Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) household survey has shown that in Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, one in five people has experienced or knows someone who has experienced sexual extortion when accessing government services such as health care or education (Transparency International 2019d; Transparency International 2019e). In Asia, GCB data suggests that one in seven people reported having experienced or know somebody who experienced sexual corruption (Transparency International 2020b). A 2019 survey in Zimbabwe found that 57% of female respondents reported that they had to offer sexual favours in exchange for jobs, medical care and or when seeking placements at schools for their children (Transparency International Zimbabwe 2019).

Recent research into corruption in the education sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo found that 48% of respondents thought that the mothers of schoolchildren were at risk of sexual corruption when interacting with school staff (Bergin 2024: 23-24). A nationally representative survey of women in North Macedonia showed that 21.5% of respondents expressed the view that sexual extortion by public officials happens ‘very often’. While 5.4% of those surveyed stated they themselves had been victims, only 37% of those women stated they would be willing to report their case to the authorities (OSCE 2021a: 47-48).

Sexual corruption can affect both men and women (Lundgren et al. 2023); one recent study spanning five African countries identified one case involving a male victim (Bergin 2024: 47-49). Nonetheless, the empirical evidence clearly indicates that sexual corruption disproportionately affects women and girls (Bjarnegård et al. 2022). One study from South Africa found that 84%of victims of sexual corruption were women (Hlongwane 2017).

Their biological sex and gender identity can make women and girls targets of sexual abuses of power. As a migrant man interviewed for a report on corruption during irregular and forced migration observed, “for us men, we give [officials] money, but for women it’s double the price. They always have to pay this double price” (Merkle et al. 2017).

Moreover, gender discrimination can mean that generally women possess fewer – or have less control over – financial assets. Gender income and wealth inequality can leave women less able to pay bribes in cash, which can lead to corrupt individuals abusing their positions of authority to coerce and exploit women into sexual activities in lieu of cash bribes (Transparency International 2020a; Mumporeze et al. 2019). A South African woman in Johannesburg reported that “if I don’t have money to bribe the water utility staff he will sexually abuse me, because that’s the only valuable thing I can give him” (NDP-SIWI Water Governance Facility 2017).

These testimonies underline the fact that monetary forms of corruption and sexual corruption do not exist in isolation from each other. Perpetrators may demand one when the other is not available, but there are reportedly cases in which women have been coerced into paying both a bribe and performing a sexual act (Bergin 2024: 47-49).

An important risk factor is that perpetrators of sexual corruption – often public officials – may assume that women lack recourse to justice, are unaware of their rights or have no formal employment protection (Boehm and Sierra 2015). As such, certain types of women for whom that is more likely to be the case may be more exposed to sexual corruption than others (Hagglund and Khan 2024). Focus groups participants in Rwanda expressed the view that widows, single women and divorced women were more likely to be targeted (Bergin 2024: 47-49). Other risk factors are thought to be poverty (UNODC 2020), illiteracy, living in rural areas, as well as markers of precarity including disability status and the absence of legal protection that many migrants experience (Bergin 2024: 47-49; Caarten et al. 2022; Merkle et al. 2017; Merkle et al. 2023). In addition, individuals with various diverse sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics (SOGIGESC) are thought to be especially vulnerable to sexual forms of corruption (Abut 2022).

Sexual corruption occurs across a wide range of settings, particularly at “pressure points” where the livelihood of victims or their family is at stake, such as when trying to obtain land deeds, work permits, access to water, shelter, health care, jobs or qualifications (Bergin 2024: 47-49; Merkle et al. 2023). Evidence indicates that many sectors are affected, including health, education, land, sports, water and sanitation, the judiciary and law enforcement (McDevitt 2022; Merkle et al. 2023; Sundström and Wängnerud 2021; Transparency International 2020a). Krook (2020) has documented how even women standing for political office – women who frequently come from more advantaged sections of society – have been exposed to sexual corruption in exchange for acceptance onto parties’ lists of candidates and the receipt of party support for election campaigns.

While the impact of sexual corruption is yet to be adequately documented, it can be partly inferred from the vast literature on the impact of other forms of gender-based violence such as rape and sexual exploitation. Sexual extortion is a form of sexual abuse that survivors may experience as a traumatic act of violence, and could result in similar social, physical and mental health consequences. Indeed, growing evidence from multiple countries suggests that sexual corruption has severe psychological, physical, economic and social impacts on survivors. These include dropping out of school, pregnancy, unsafe abortions, contracting sexually transmitted diseases, mental health problem, decreased credibility in the community, leaving a well-paid job or forgoing public services to avoid exposure to further abuse (Bergin 2024: 47-49; Caarten et al. 2022; Mumporeze et al. 2019; Transparency International 2020a). The dramatic impact this can have on an individual’s psychology and sense of self-esteem is documented in case studies on sexual corruption in the police force and medical universities in Madagascar described by McDonald and Jenkins (2021: 27-31). Other research from Madagascar has documented that victims of sexual corruption in schools, who are typically minors, often go without any psychological treatment or support from trained social workers and psychologists (Bergin 2024: 47-49).

Role played by women in curbing sexual corruption

There are substantial legal, social and cultural barriers to challenging sexual corruption.

Sexual corruption is notoriously difficult to prosecute (Eldén et al. 2020: 55). Legislation or codes of conduct in many countries fail to define, account for or forbid the practice of those in positions of entrusted power from making the provision of a service or benefit conditional on a sexual act (France 2022). Sexual corruption can be both a form of corruption and gender-based violence (Merkle 2024), and most jurisdictions rely on a patchwork of legislation that does not cover all expressions of sexual corruption described by Bjarnegård et al. (2024a).

Eldén et al. (2020: 49-50) maintain that power asymmetries between victim and perpetrator in cases of sexual corruption imply that consent has been coerced instead of provided freely. Yet Eldén et al. (2020) acknowledge that prosecutors can face evidentiary challenges around the issue of consent under the gender-based violence framework (see also UNODC 2020: 46), particularly as non-physical forms of coercion may not be recognised (Carnegie 2019). At the same time, under the anti-corruption legal framework, some countries only criminalise corruption when monetary bribes are involved, and victims could potentially be prosecuted as a bribe-giver (France 2022). Recent work by Bauhr et al (2024a) has shed light on how different jurisdictions (Nigeria and Brazil) are currently attempting to strengthen their legislative framework to make sexual corruption easier to prosecute while safeguarding victims.

Sexual corruption in the judicial system is especially concerning given that it can make it harder for survivors to access justice (de Castro 2018). In addition, many cases are not reported due to a fear of retaliation as well as social stigma and cultural taboos (World Vision 2016). Other barriers to reporting incidents of sexual corruption include shame, fear of facing retaliation, experiencing re-traumatisation and the unavailability of a gender-sensitive reporting mechanism that recognises the unique aspects of the crime (Sundström and Wängnerud 2021: 16). Tellingly, a large survey in the Madagascan education sector found that although 80% of respondents believed citizens were free to report corruption, only 25% believed women and girls had a safe space in schools to report sexual corruption (Bergin 2024: 47-49).

Even where cases of sexual corruption are reported, finding evidence in the absence of witnesses tends to be difficult. Moreover, although mechanisms to address sexual corruption do exist in some countries, such as culpable staff being transferred to another institution, these rarely reflect the severity of the crime (Bergin 2024: 47-49).

A multipronged strategy is therefore required to reduce rates of sexual corruption. This could involve establishing legal definitions and penalties to sanction sexual abuses of power and strengthening gender-sensitive reporting channels. Some authors suggest incorporating provisions expressly forbidding sexual corruption into organisational codes of conduct as a short-term “bridge” until legal frameworks can be amended to address the phenomenon (OSCE 2021a: 48).

In addition, preventive efforts could seek to deepen women’s financial and social independence as well as engage both men and women in a cultural shift to overhaul traditional social norms that often blame the victim in cases of sexual corruption (Bergin 2024: 47-49; Eldén et al. 2020: 96; Hagglund and Khan 2024; Merkle et al. 2023; OSCE 2021a: 47). In particular, Bjarnegård et al. (2022) argue that challenging “informal descriptive norms about masculinity” and “informal injunctive norms about female sexual behaviour” is central to reducing impunity for perpetrators of sexual corruption. Awareness-raising campaigns could also target local communities, journalists and government officials, who research has shown are able to recognise cases of sexual extortion but do not perceive these as a form of corruption (OSCE 2021a: 46, 49).

Impact of corruption on women’s access to justice

Impact of corruption on women’s access to justice

Historic, structural discrimination against women and girls has resulted in unequal access to resources, justice and rights in many parts of the world. Discrimination deprives women of opportunities to participate fully in social, economic and political life, including in the justice sector. Women are underrepresented in both formal and informal justice systems around the world (United Nations 2024). The gender imbalance is especially pronounced in higher courts (Malik 2021; OECD 2023) and transitional justice mechanisms (UN Women 2020: 34).

A review of the literature indicates that firstly, women can be more affected by corruption in the justice sector, and secondly, gender inequalities undermine women’s ability to report corruption.

How corruption affects women seeking justice

Nyamu-Musembi (2007) has pointed out that in settings where paying bribes to judicial or administrative staff becomes a prerequisite to access the court system, women’s relatively weaker access to and control over financial resources means they are more frequently denied justice. This is especially true in court cases in which the judicial ruling is essentially ‘for sale’ to the highest bidder and where one litigant is a woman and the other is a man (OSCE 2021b: 15). Feather (2022) documents how judicial corruption in Morocco has enabled underage and polygamous marriages,6f9c47a14761 while granting men impunity for sexual offences and domestic violence. Similarly, several studies in Uganda found that women have little trust in the police to properly investigate cases of rape and domestic violence due to corrupt practices, such as the perpetrators paying off the police (McGranahan et al. 2021; Transparency International 2016: 10). In Uganda, this reportedly led affected women to avoid contacting authorities altogether.

Research suggests that lower courts are particularly susceptible to corrupt practices that produce gender discriminatory outcomes (UN Women 2018: 143). Indeed, in some settings, “corruption, abuse of power and lack of professionalism in formal justice institutions, as well as cultural and family pressures that discourage formal complaints” drive women towards informal justice mechanisms (UN Women 2018: 252).

Moreover, women may be at a greater risk than men of being subjected to extortive forms of corruption when trying to access justice (OAS 2022: 26; OSCE 2021b: 15). Entrenched socio-economic inequalities between women and men can mean that women are more frequently targeted with demands for bribes from corrupt public officials (Ellis et al. 2006; UNDP 2010). This may be due to the fact that corrupt officials assume that women lack recourse to justice, are unaware of their rights or that they have no formal employment protection (Boehm and Sierra 2015). Such assumptions are often unfounded. Nonetheless, such calculations on the part of crooked officials are premised on real and widespread discriminatory practices (UNDP 2010: 8-12).

Gender inequality can be particularly stark when legal proceedings relate to property (Transparency International 2018). A 2015 study from Ghana found that 40% of women said that corruption in the legal process obstructed their access to land, compared to 23% of men (UN Women 2020: 20). Unsurprisingly, the lack of access to justice is associated with higher rates of poverty and lower civic participation (UN Women 2020: 38).

Not all forms of corruption impeding women’s access to justice are pecuniary. The UNODC Global Judicial Integrity Network (2019: 15-18) has documented multiple instances of sexual corruption that targeted women during judicial proceedings and interactions with judges and court administrators.

How gender inequalities impede women’s ability to report corruption

Despite suffering disproportionately from the gendered impact of corruption, emerging data indicates that women appear to be less likely than men to report corruption or to have their report of corruption registered or actioned. While not a representative dataset, between 2011 and 2021, only 34% of people filing complaints at Transparency International’s global network of Advocacy and Legal Advice Centres were women (Transparency International 2021: 7).

This lower reporting rate is thought to be the result of multiple factors that combine to “undermine women’s sense of personal efficacy and […] impede their ability to report and challenge corruption” (Transparency International 2021: 8).

First, barriers to women reporting corruption include the well-founded perception of gender bias in the processing of corruption cases; there is evidence that corruption complaints filed by women tend to be dismissed more frequently than those filed by men (Transparency International 2020a: 30). A recent study on sexual and reproductive health of adolescent girls and young women living in slums in Uganda found that whether law enforcement agents took a reported violation seriously depended on an individual’s gender, wealth, education and age (McGranahan et al. 2021). Similarly, recent research in Madagascar revealed that multiple grounds of discrimination intersected to prevent women with albinism from challenging corrupt practices and demanding redress from the justice system (Barnes 2024: 79-80). Combined with their overall underrepresentation in many justice systems, this fact might explain why women seem to hold more pessimistic views than men about the utility of reporting corruption (Transparency International 2021: 13).

Second, due to their social roles and gender inequities, women may lack financial resources or time to report corruption and become entangled in lengthy legal proceedings. Data from a household survey conducted in Europe in 2016 found that women were marginally less likely than men (36% to 39%) to report corruption if they had to attend court to provide evidence (Transparency International 2021: 8).

Third, women may be less aware of their rights and of suitable channels to report corruption (Women Development Organization 2021; 22-23; Transparency International 2021: 3). UNDP (2010: 8) has reported that discriminatory practices in schooling in some countries can lead women to have a have more limited awareness of their legal entitlements. Data from the Global Corruption Barometer revealed that fewer women than men knew of their right to information in Asia (46% of men to 43% of women), while in Europe 18% of women stated they did not know where to report instances of corruption compared to 15% of men (Transparency International 2021: 9-10).

Fourth, women appear to be more likely than men to fear reprisals when reporting corruption. Representative survey data has shown that in the EU, Latin America and Asia, women are less likely to think that people can report corruption without fear of retaliation, typically by around 5 percentage points (Transparency International 2021: 6). In this respect, the lack of gender-sensitive reporting mechanisms available to women is a real problem (Transparency International 2016: 10), which is particularly acute in cases of sexual corruption (de Castro 2018). This is due to the social stigma and cultural taboos associated with these types of offences (World Vision 2016), the difficulty in collecting evidence,f1c477c57554 the risk of re-victimisation and having to re-live the trauma, discriminatory myths and sexual stereotypes and, in some countries, even the risk of being prosecuted for paying a (sexual) bribe or committing adultery (Transparency International 2020a).

Role played by women in limiting the impact of corruption in the justice sector

Increasing women’s representation in law enforcement and the judiciary is one potential measure to reduce the impact of corruption on women’s access to justice. Malik (2021) contends that efforts to increase the number of women judges can both engender greater public trust in the judiciary and ensure that judicial outcomes are more gender sensitive. In her study on Burundi, Niyonkuru (2021) concurs, arguing that greater gender diversity in the judiciary would improve women’s access to justice.

In terms of law enforcement, there have been some attempts to establish women’s only police units in the name of reducing corruption and increasing reporting sexual offences, including in Mexico and India (AFP 2015; Watson and Close 2016). Negative effects of such policies have, however, been documented; Jassal (2020) concluded that the introduction of all-female police stations in India led to standard police stations refusing to register gendered crimes as well as to increased travel costs for women seeking justice. Similarly, in Pakistan, Ahmad (2019) finds that female police officers have not been able to reduce police corruption.

More generally, a common recommendation in the literature is for judges, prosecutors and law enforcement personnel to receive training on gender mainstreaming with regard to corruption-related offences (OAS 2022: 64). Improving enforcement responses to instances of corruption within the justice system is thought to be another important step to building trust among women and broadening access to justice (UN Women 2018: 90).

When it comes to increasing the rate of corruption reporting by women, a common proposal is to make reporting channels more accessible, affordable and safe (Zúñiga 2020). The Practitioner’s Toolkit on Women’s Access to Justice Programming stresses that “complaints mechanisms should be located within justice institutions staffed by independent and trained personnel to address allegations of corruption, abuse of power and sexual harassment” (UN Women 2018: 94). Raising community awareness of these mechanisms and making them easily accessible is an important consideration (Women Development Organization. 2021: 23). In this respect, Transparency International chapters in multiple countries have created mobile clinics to collect and respond to reports of corruption, sexual offences and other wrongdoing from women in rural areas (Transparency International 2021: 14).

Women’s participation in policy-making and government

Impact of corruption on women’s political participation

Corruption and women’s political representation

Women worldwide are underrepresented in the political sphere; as of 2024, only 26.9% of parliamentarians are women (IPU 2024; UN Women 2024). Corruption is a direct barrier to women’s participation in politics, affecting both active and passive suffrage.

In terms of active suffrage, some studies suggest that women tend to be more targeted by vote buying practices, especially through the provision of in-kind “gifts” (Cigane and Ohman 2014). As such, corruption in electoral processes can distort and limit women’s opportunities to cast their vote in a manner that informs political processes and decision-making (McDonald and Jenkins 2021: 26).

In terms of passive suffrage, there is some evidence that in settings with high levels of political corruption, women are less likely to enter the political arena. A comparative study of 18 European countries, for instance, found where corruption is high, the number of elected women is relatively low (Sundstrom and Wangnerud 2014).

Research from different electoral systems indicates that political recruitment of women is more difficult in corrupt or clientelistic environments in which women are likely to be excluded from male-dominated political networks and power brokering arrangements (Grimes and Wangnerud 2015; Sundstrom and Wangnerud 2014). Bjarnegård (2013) argues that, for historical reasons, corrupt political networks are generally male-dominated, and the requirement of these networks to maintain both secrecy and intra-group trust incentivises them to recruit other men who exhibit norms familiar to them. Collusive corruption between male insiders in these patronage networks has been shown to throttle women’s access to political and economic opportunities (Bauhr et al. 2018; Galli et al. 2016).

Women’s lack of political representation heightens the risk that policymakers make decisions which are not gender inclusive. At best, women may rely on policies and programmes to address women’s specific needs that have been designed by men. At worst, such as in settings in which political corruption is systemic, male-dominated patronage networks may neglect the interests of women and girls completely (Bergin 2024: 36). Such exclusion could leave groups such as women more vulnerable to the impact of corruption and misgovernment.

Impact of corruption scandals on women’s political representation

One issue that is subject to increasing scholarly scrutiny is the effect of revelations about incumbents’ corruption on women’s political participation and representation.

In their study on local elections in Brazil, Diaz and Piazza (2022) find that where corruption in public office is exposed, more women are inspired to stand for public office against corrupt incumbents, especially where the implicated incumbent is male. However, corruption revelations themselves do not enhance female candidates’ chances of winning elections. The authors suggest two reasons for this. First, they find that institutional barriers for political newcomers, such as incumbency advantage, disproportionately affect women. Second, female candidates struggle to mobilise the same level of campaign finance as their male opponents, particularly in corrupt localities, due to gender norms that serve to impede women’s entry in politics.

A study by Baraldi and Ronza (2024) finds that after Italian city councils are dissolved in response to identified mafia infiltration, level of corruption decreases, while the probability that the women are elected as councillors and mayors sharply increases. This suggests that, contrary to Diaz and Piazza’s (2022) findings from Brazil, women may be more likely not only to contest elections in the aftermath of a corruption scandal, but also to win them. The authors suggest this is due to reduced voter bias against women as policymakers in the wake of corruption cases (Baraldi and Ronza 2024).

Similarly, Petherick (2019: 164) finds that when voters in Brazil become aware of corruption on the part of an incumbent male office holder, voter demand for female candidates increases. Specifically, when municipal elections are rerun due to vote-buying being detected, women candidates generally perform better in the replayed election (Petherick 2019: 24). She links this to a broader literature on Latin American politics in which distrust in government “encourages support for female leadership as an alternative to the discredited (male) establishment” (Petherick 2019: 64). In her view, the phenomenon is explained by voters’ gendered stereotype of “female incorruptibility” (Petherick 2019: 72).

Indeed, it appears that many politicians are conscious that voters associate women with more ethical behaviour and expect higher standards from them. Armstrong et al. (2022) find that in countries in which corruption is believed to be increasing but where democratic accountability is high, heads of government are more likely to appoint a woman as finance minister. The authors interpret this as a kind of virtue signalling on the part of government to voters to demonstrate their commitment to “quelling economic malfeasance”, given the popular stereotype that women are less corrupt than men (Armstrong 2022).

The flip side of this is that once in office, relative to men, voters may hold women to higher ethical standards and punish them more severely for perceived wrongdoing (Barnes and Beaulieu 2014; Barnes and Beaulieu 2018). An experimental study by Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al (2017) and case studies by Pereira (2020) on Mexican and Brazilian elections find that voters are likely to sanction female office holders more harshly for corruption than their male counterparts. Eggers et al (2018) find that while female politicians in Britain do not face significantly greater punishment for misconduct overall, women voters are more likely to sanction female politicians for unethical behaviour.

Merkle and Wong (2020) point to the correlation between individuals’ attitudes towards female political leadership and their tolerance of corruption. They therefore propose interventions that focus on shifting gendered norms and patriarchal attitudes at the grassroots level could contribute to anti-corruption efforts.

Role of women’s political participation in preventing and curbing corruption

Women’s political participation, as exercised through both active and passive suffrage, can potentially contribute to lower levels of corruption.

Active suffrage

There is some indication that women are more prepared to use their vote to evict corrupt politicians and support ‘cleaner’ (or at least ‘fresher’) candidates. In a study of 21 European countries, Alexander et al. (2019) conclude that women are more likely than men to vote for alternative candidates where their preferred party is embroiled in a corruption scandal. The effect is stronger in countries in which social spending is high, which may not be surprising, as other studies suggest that female voters are more likely to prioritise public service delivery than men (Stensöta and Wängnerud 2018; Ennser-Jedenastik 2017; Smith 2014), and have a “greater propensity to base voting decisions on social concerns” (Bauhr and Charron 2020: 94).

Passive suffrage

The relationship between the presence of women in positions of political power and levels of corruption has been a topic of intense study in the past twenty years. In addition, certain countries have introduced measures to increase women’s political opportunities. Brazil, for instance, has stipulated that parties assign female candidates a minimum 30% of advertising time and campaign funds, although the actual impact of these quotas is not yet clear (Diaz and Piazza 2021: 19). Some scholars, like Soyaltin-Colella and Cin (2022: 12), claim that the notion of promoting women’s political participation as an anti-corruption measure (particularly through gender quotas) is tokenistic and masks underlying gender biases.

Nonetheless, numerous articles have made the case that there is a strong empirical association between women’s political representation and control of corruption, with some studies indicating that there is a causal link between increasing the number of women in elected office and a lower incidence of corruption (Alexander et al. 2023; Bauhr and Charron 2021; Bauhr et al. 2018; Bauhr et al. 2024b; Brollo and Troiano 2016; Correa Martinez and Jetter 2016; de Barros Reis et al. 2024; Esarey and Schwindt-Bayer 2018; Esarey and Schwindt-Bayer 2019; Jha and Sarangi 2018). Various causal mechanisms that could explain this observation have been proposed and tested.

Dollar, Fisman and Gatti (2001) pointed to behavioural studies that found women to be more trustworthy and public-spirited than men. This school of thought became associated with what was termed the ‘fairer sex’ theory in the anti-corruption field. Recent literature on the role of female policymakers in preventing corruption presents a more nuanced picture than that put forward by the earlier ‘fairer sex’ theoretical papers.

Studies have challenged the idea that women are less corruptible than their male counterparts, particularly as they can become initiated into corrupt practices once in office (Barnes and Beaulieu 2018; Mywangi et al. 2022). For instance, in a study of French municipal elections, Bauhr and Charron (2021) found that while newly elected women mayors are associated with lower corruption risks in municipal procurement, gender differences in the extent of corruption risk are negligible in municipalities in which women mayors have been re-elected. Bauhr and Charron (2020) suggest that this indicates that women eventually adapt to the corrupt networks to survive in office, not least as newly elected female representatives who aggressively target corruption may reduce their chances of re-election by generating hostility on the part of embedded corrupt elites (Bauhr and Charron 2021).

Other potential explanations for why women in power appears to frequently result in lower rates of corruption have been proposed, including by Bauhr et al (2018) who observed that the election of women to local councils in 20 EU countries was strongly negatively associated with the prevalence of both petty and grand corruption. They contend that female representatives seek to further two separate political agendas once they attain public office: first, the improvement of public service delivery in sectors that tend to principally benefit women, and second, the breakup of male-dominated patronage networks.

Regarding the former, numerous studies corroborate the idea that women elected to public office prioritise social spending and service delivery (Bolzendahl 2009; Ennser-Jedenastik 2017; Merkle 2022; Smith 2014).

Regarding the latter, a body of work has provided some support for the marginalisation theory that women are less likely to partake in corrupt transactions simply because of their exclusion from male-dominated elite networks (Barnes 2016; Bjarnegård 2013; Goetz 2007). In this view, female political newcomers may be less bound to existing clientelist networks and – at least for an initial period after they take office – this may offer a window of opportunity to disrupt established patterns of corrupt behaviour.

There is some empirical evidence that lends support to this notion. A study in Argentina found that women elected to parliament are more likely than their male counterparts to represent alternative political parties to the traditional parties associated with clientelist networks (Franceschet and Piscopo 2013). In Mexico, researchers found that women are more likely than men to start their political careers as members of civil society rather than rising up through the ranks of established patronage networks (Rothstein 2016 cited in UNDOC 2020: 37). These findings imply that female politicians may cater to different constituencies and could have incentives to break up established patronage networks their opponents rely on.

Bauhr and Charron (2020: 92) and Bauhr and Schwindt-Bayer (2024) thus propose that a virtuous circle exists; in systems in which political recruitment is not controlled through corrupt, patronage-based systems women are more likely to enter elected office (see also Stockemer and Sundström 2019; Sundström and Wängnerud 2014), and, once there, they can help to further destabilise networks that perpetuate political corruption.

Finally, it is worth noting that the relationship between the presence of women in positions of political authority and the extent of corruption is mediated by regime type; the association is stronger in democracies than autocracies and in parliamentary systems than presidential ones (Esarey and Schwindt-Bayer 2017; Bauhr and Schwindt-Bayer 2024; Stensöta and Wängnerud 2018).

- The authors speculate might be due to dedicated health programmes targeting women and girls implemented by governments, international organisations and NGOs.

- Interestingly, evidence from Ghana suggests that women are more likely than men to pay bribes in non- pecuniary form, such as food, drink or livestock. (UNODC 2022: 21)

- Other terms have been used to refer to this behaviour, including transactional or survival sex (Merkle 2024).

- While polygamous marriages are legal under certain strict conditions in Morocco (UNDP 2019), judicial corruption appears to play a role in undermining the enforcement of existing rules intended to restrict the practice (Feather 2022).

- Finding evidence in the absence of witnesses tends to be difficult and often laws do not recognise non-physical forms of sexual coercion (Carnegie 2019).